2a: Understanding of teaching, learning, and/or assessment processes

Throughout my career, I have focused on designing learning environments that foster engagement, critical thinking, and practical application. As the coordinator of the Graduate Certificate in Learning Design (GCLD), I had the opportunity to shape an innovative curriculum that reflected modern pedagogical approaches while meeting the specific needs of adult learners. My first guiding principle was the idea of constructive alignment. This approach was inspired by Biggs (2014) and Biggs and Tang’s (2014) work which specifically refers to aligning learning and teaching activities with learning objectives and assessment tasks. I think this is especially important in professional contexts, such as learning design; I’ve been frustrated in the past with what I’ve felt were assessment tasks that lacked relevance to professional contexts, so this is something that I wanted to be mindful about in designing this course.

One example of my innovative decision-making was to implement flipped learning in the GCLD program. Drawing on the work of scholars like LaFee (2013), I structured the course so that students engaged with the learning content asynchronously—through readings, multimedia resources, and interactive content—prior to live sessions. This allowed live sessions to be more interactive, serving as a space for application, discussion, and deeper analysis. In the live sessions, students worked in groups to solve real-world learning design problems, using the theories and concepts they had previously explored.

This approach was particularly beneficial because it allowed learners to control the pace of their initial engagement with the material, which was crucial for the diverse cohort, many of whom were balancing work and family responsibilities. It also aligned with best practices for adult learning, which emphasize autonomy, practical application, and collaborative problem-solving.

In terms of assessment, I integrated authentic assessments that aligned closely with industry practices. I chose to adopt a portfolio approach for the assessment tasks across the whole course. In each subject, students complete a ‘learning object’ directly related to work as a learning designer. In addition, they complete a reflection where they document their learning based on that task. Instead of traditional exams or essays, students were asked to design interactive learning objects, such as multimedia learning modules or assessment rubrics, which they could later showcase in professional portfolios. This not only reinforced the course content but also provided students with tangible evidence of their learning that they could present to potential employers.

This is an example of a student assessment task, using Rise:

https://rise.articulate.com/share/aPag–mp_0bBY5wmHeerNv4Et5UZ-wIn#/

2b: Understanding of your target learners

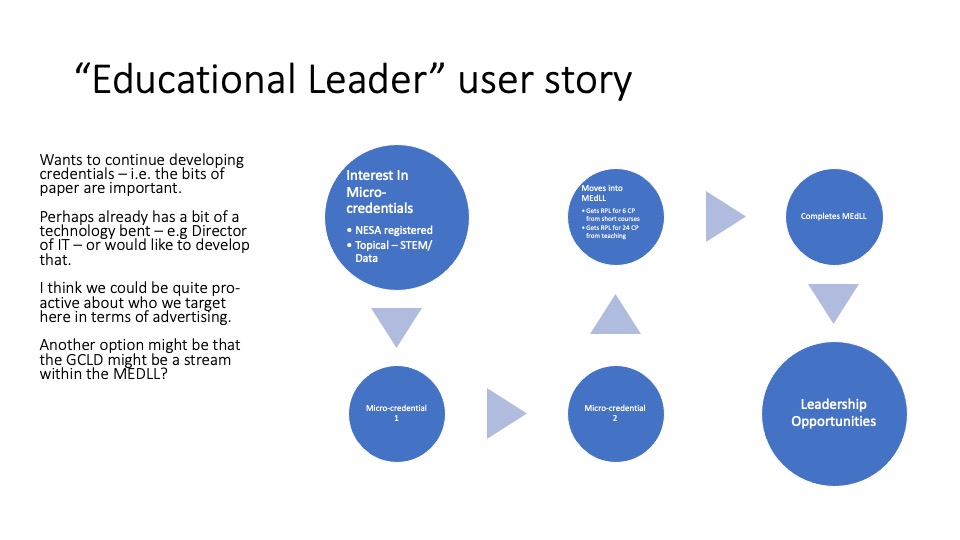

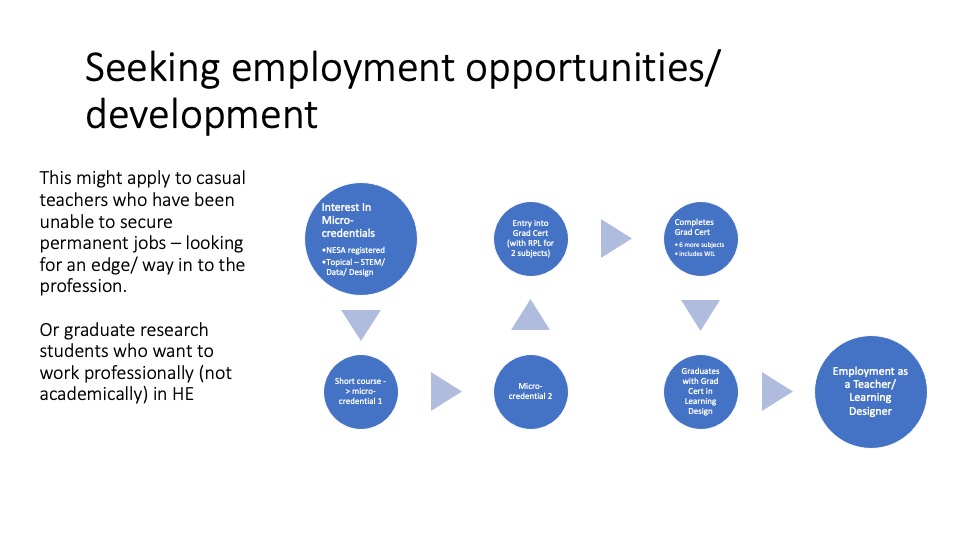

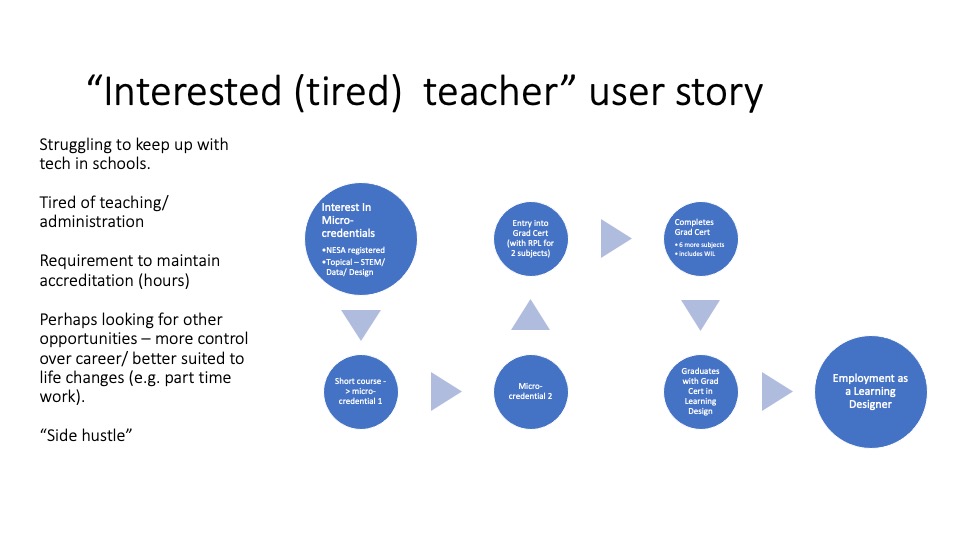

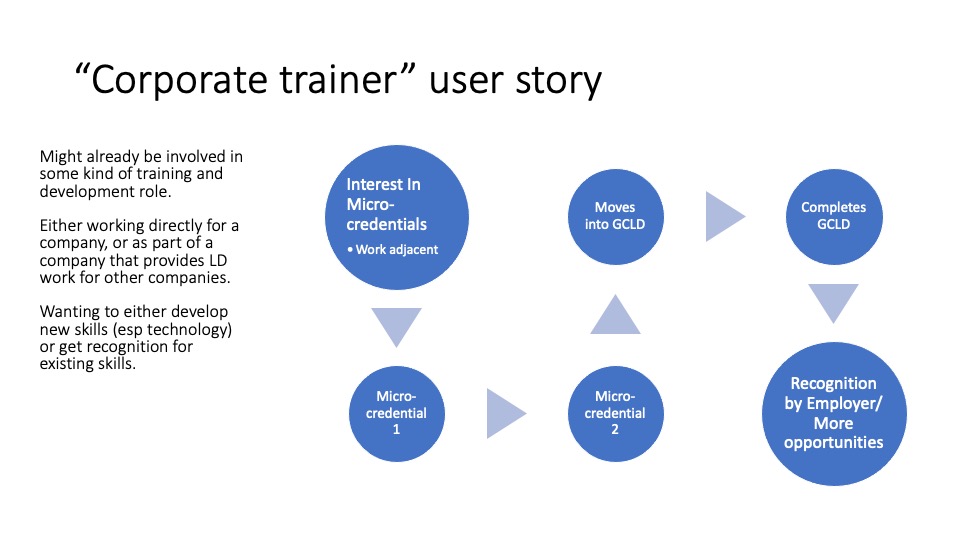

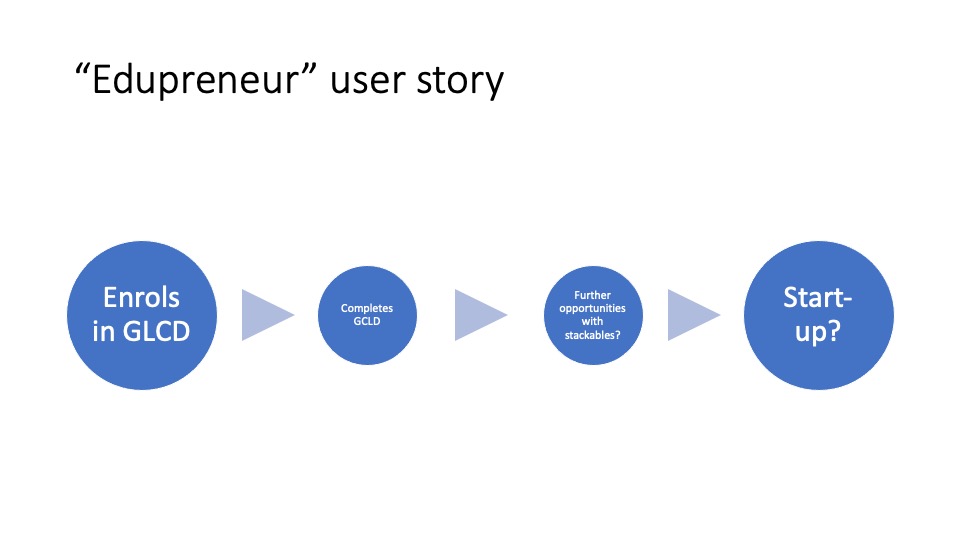

When designing learning experiences, I have consistently applied a learner-centered approach, ensuring that the content, delivery, and assessments are tailored to the specific needs of my students. For the GCLD, I conducted a series of interviews with potential learners to understand their motivations, challenges, and prior experiences. This allowed me to create learner personas, such as “the career changer,” “the part-time student,” and “the corporate learning and development professional.”

For example, many students enrolled in the GCLD were transitioning into the field of learning design from other professions, such as teaching or corporate training. These learners often needed more flexible, modular learning options, as well as practical, immediately applicable skills. In response to this, I developed a course structure that was broken into three-credit subjects delivered sequentially, allowing students to complete shorter, focused learning experiences that fit into their busy schedules. This structure was particularly useful for those juggling multiple responsibilities, as they could easily apply the knowledge and skills gained in one module before moving on to the next.

Additionally, my decision to adopt hyflex learning—a blend of synchronous and asynchronous modalities—enabled students to access the course in a way that suited their lifestyle. For example, all live sessions were recorded, and students who were unable to attend in real-time could still participate by completing equivalent asynchronous tasks. This flexibility was key to maintaining high levels of engagement and satisfaction among students with varied personal and professional commitments.

Understanding the demographic and geographic diversity of my learners also led me to make key decisions about course accessibility. Informed by research like the Bradley Report (2008), which highlighted the increasing number of university students balancing education with work and caregiving responsibilities, I ensured that the GCLD was entirely online and accessible from any location. I also emphasized the importance of universal design for learning (UDL) principles, incorporating materials that were accessible to students with disabilities and providing multiple formats for engagement, such as text, video, and interactive content.

References

Biggs, J. (2014). Constructive alignment in university teaching. HERDSA Review of Higher Education, 1, 5-22.

Biggs, J. & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching For Quality Learning At University. McGraw-Hill.